How do a singer and a musician begin a selection? Every song or piece of music has a label. That label is called a key. This stamp, or key signature, can be found immediately after the time signature on the musical staff. A key signature displays how many accidentals (also known as sharps and flats) are in a piece of music, and immediately tells the singer where to sing and the musician where to play. For each major key, there is a relative minor key.

Here are some examples of this relationship. “You Are So Beautiful“ written by Billy Preston and Bruce Fisher is in the key of F Major, while “Sexy“ performed by Black Eyed Peas is in the key of Dm. These keys are related and share the same key signature – one flat. “Unforgettable“, sung by Nat King Cole and written by Irving Gordon is in the key of G Major, while “Fallin’“ written and performed by Alicia Keys is in the key of Em. These keys are also related and share the same key signature – one sharp. “Take The A Train” written by Billy Strayhorn is in the key of C, while “I Will Survive” performed by Gloria Gaynor is in the key of Am. These related keys share the same key signature – there are no accidentals.

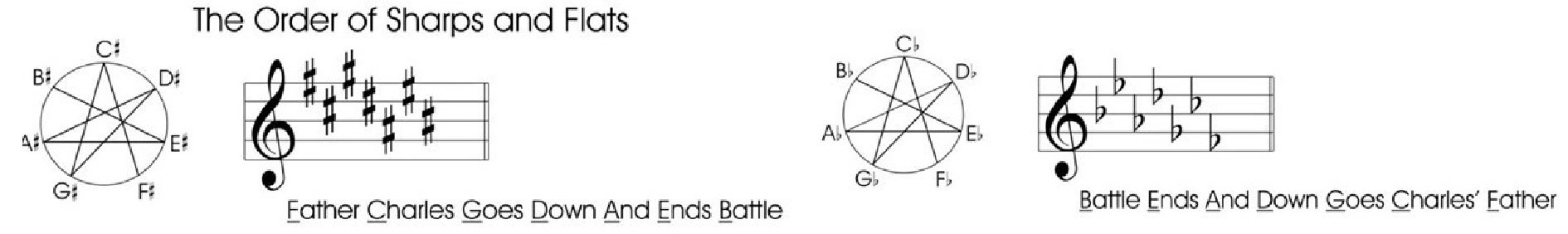

How would one know what the key is when looking at the key signature??? This is accomplished by first learning the order of sharps and flats. Besides memorizing them, there are three ways you can find the key when looking at sharps and flats: A pneumonic device, playing out the appropriate scale and isolating the accidentals, or remembering the unique rule for each.

The Order of Sharps is F, C, G, D, A, E, B. As a pneumonic device, the order could be memorized by assigning a phrase that is easily remembered. “Four College Grads Dined At Every Bakery”. With playing out the appropriate scale and isolating the accidentals, in the key of A Major, the scale would be A, B, C#, D, E, F#, G#, A. Finally, the unique rule for dealing with keys that contain sharps is to go to the last sharp and raise it by one half step. For example, the key of A Major has G as its last sharp. When you raise G# one half step, you arrive at the name of the key, which is A. This rule works with every key that contains sharps. Alternatively, if you know the key’s name, you can use that to identify its signature. To do this, you would lower the name of the key by a half step, which identifies the last sharp in the scale. Lastly, recall the order of sharps.

The Order of Flats is B, E, A, D, G, C, F. As a pneumonic device, the order could be memorized as “By Every Anointing Does God Cover Faithfully”. Playing out the appropriate scale and isolating the accidentals, in the key of Bb Major, the scale would be Bb, C, D, Eb, F, G, A, Bb. If you’re looking at the key signature, the next to the last flat is your key. In this instance, the key of Cb Major, applying the rule and playing out the appropriate scale would be Cb, Db, Eb, Fb, Gb, Ab, Bb, Cb.

To be successful in playing any instrument, one isn’t required to learn the Order of Sharps and the Order of Flats, but it is highly recommended. Chord progressions can be handled much more effectively with that foundation. This lesson speaks specifically to sight reading. Music goes to your ear before it goes anywhere else.